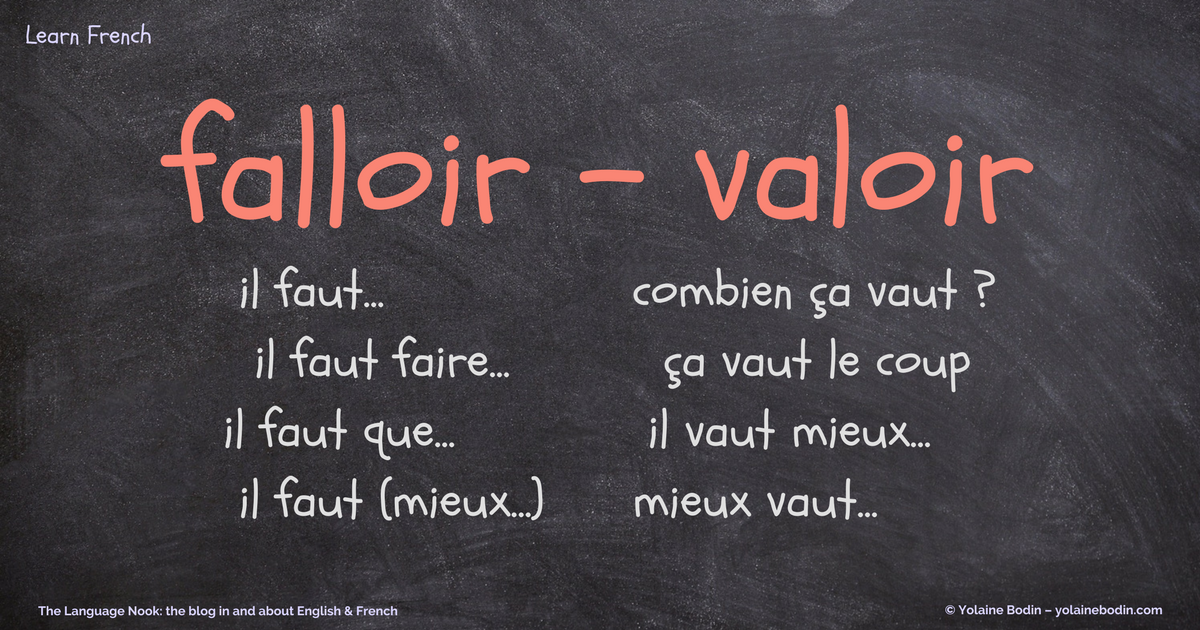

Falloir and valoir are two distinct French verbs that are sometimes confused. At this point, I would like to reassure all learners of French as a foreign language and say that even French natives may mix them up in some instances! I gather the confusion comes from the proximity of the sounds f and v.

What do these two verbs mean and how can we use them correctly?

Falloir conveys an obligation, need or necessity. It is an impersonal verb. This means that it can only be conjugated with the pronoun “ il ” and in that case “il” does not represent anyone or anything in particular: it is the same as in “il pleut” (it’s raining).

Falloir can be followed:

→ by a noun (with a determiner):

- Il faut de la farine pour faire des crêpes. (You need flour to make pancakes.)

- Il me faut un oreiller pour dormir. (I need a pillow to sleep.)

→ by a verb in the infinitive form:

- Il faut sortir les œufs du frigo. (You have to/need to take the eggs out of the fridge.)

- Il faut partir maintenant. (You must go now.)

→ by a verb in the subjunctive form:

- Il faut qu’elle vienne tout de suite (She must come immediately)

- Il faut que vous appeliez le docteur. (You must call the doctor)

Valoir can mean to be worth. It is the verb you need for example to ask how much something costs, in other words how much it is worth:

- Combien vaut ce vélo ? (How much is this bike?)

You can also use it in expressions like valoir le coup or valoir la peine to say something is worth doing or not.

Imagine you are talking about a city you visited last weekend:

- Ça vaut vraiment le coup d’y aller, c’est magnifique ! (It’s really worth visiting, it’s beautiful!)

Now imagine you have worked hard on a project but the result is disappointing. Then you can say:

- Ça ne valait pas la peine de travailler autant, quel gâchis ! (It wasn’t worth working so hard, what a mess!)

Another meaning of valoir is better to, or preferable. In this case, you use the impersonal pronoun “il” in the expression il vaut mieux. You can also begin your sentence directly with “mieux” and use the phrase mieux vaut:

- Il vaut mieux partir avant qu’il fasse nuit. (We’d better go before it gets dark.)

- Mieux vaut partir tout de suite. (It’s preferable to leave right away.)

This last usage –il vaut mieux– is the one that seems to create some confusion where some people use falloir instead. Indeed, some tend to say “il faut mieux” to mean “it’s better to”. That is what is called a barbarism, i.e. an incorrect use of the language!

Be careful not to use “il faut mieux” when what you want to say is it’s preferable or one had better do something.

However, if you want to express an obligation, necessity or need to do something better, then you will use falloir for the necessity followed by the equivalent of better, i.e. mieux and the verb, or the verb and mieux. Both word orders are correct. For example:

- Il faut mieux travailler = Il faut travailler mieux. (We must / need to work better)

Careful! Note the difference between these two sentences:

- Il faut mieux manger. = Il faut manger mieux. → We need to eat better (we must have a better diet).

- Il vaut mieux manger. → We’d better eat (… if we want to survive!)

Also note that with falloir + mieux, you can change the word order and put mieux before or after the verb. This will not change the meaning. Yet with valoir, the order of the words cannot be modified.

Now, let’s take this opportunity to look at two French proverbs using falloir and valoir:

- Il faut battre le fer pendant qu’il est chaud. (Make hay while the sun shines.)

- Mieux vaut tard que jamais. (Better late than never.)

If you know other proverbs and sayings using falloir and valoir, feel free to share them in the comments section below this article.

There you are! You now master the difference between falloir and valoir. Congratulations! 😀

Why your strange translation of: “Il faut battre le fer pendant qu’il est chaud”? Shouldn’t it be: “strike the iron while it’s hot”?

Thank you for your comment. It is true, one another way to translate “il faut battre le fer pendant qu’il est chaud” is “Strike while the iron is hot”. Obviously, it is actually closer to the French idiom since the metaphor is similar, but “Make hay while the sun shines” conveys the same meaning and I chose that one only because it seems to be more commonly used, at least in Britain. Maybe there are other English speaking countries where “Strike while the iron is hot” is more common than “Make hay while the sun shines”?